Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the anatomical features of a long bone.

- Describe the general structure and function of long bones.

- Explain the roles of compact bone, spongy bone, and bone membranes.

Introduction

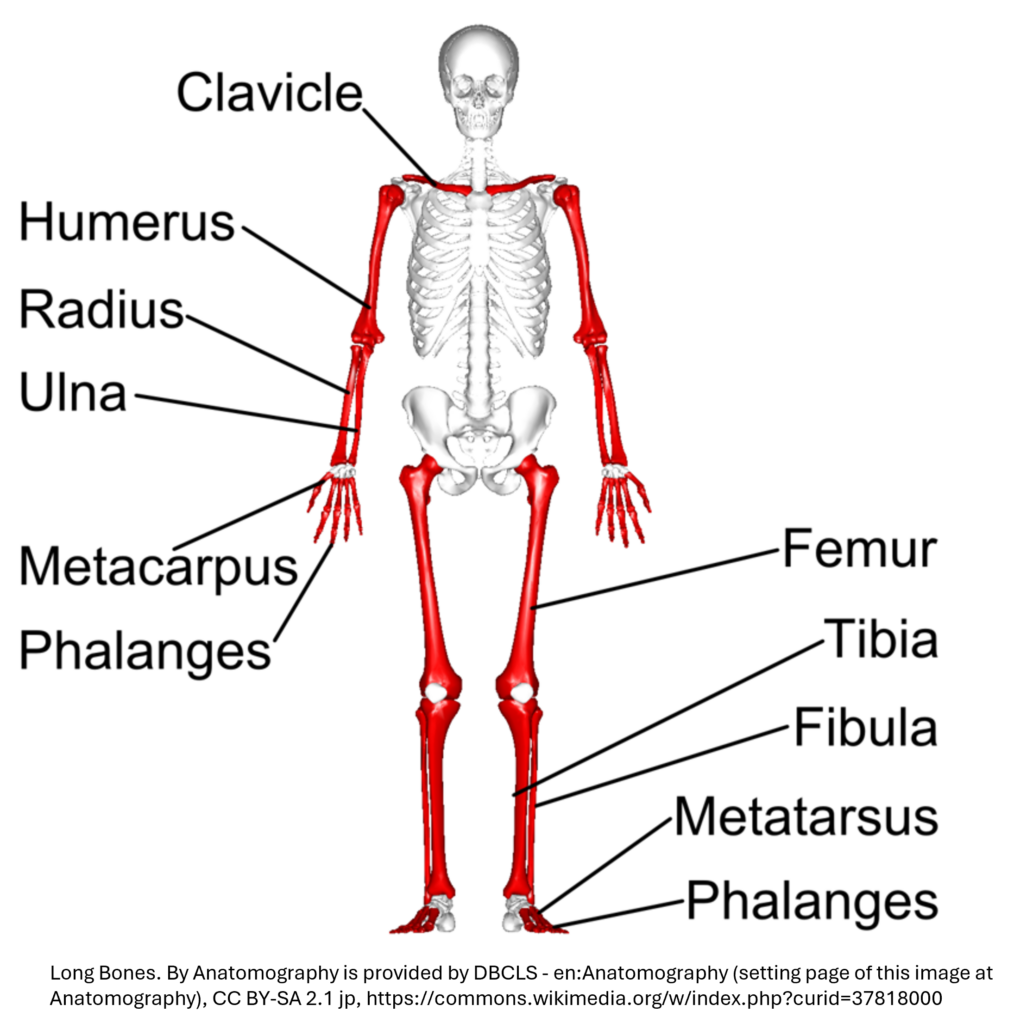

Long bones are those that are longer than they are wide, and they include bones in the arms, legs, fingers, and toes. These bones play a vital role in movement and support, especially the femur and tibia, which bear most of the body’s weight during daily activities.

In this section, you’ll explore the gross anatomy of a typical long bone, focusing on key structural regions like the diaphysis (shaft), epiphyses (ends), and surrounding layers such as the periosteum.

Understanding these features is essential not only for grasping how bones grow, repair, and function, but also for interpreting X-rays, diagnosing fractures, and recognizing growth-related changes in the skeleton.

Let’s first break down the key regions of a long bone.

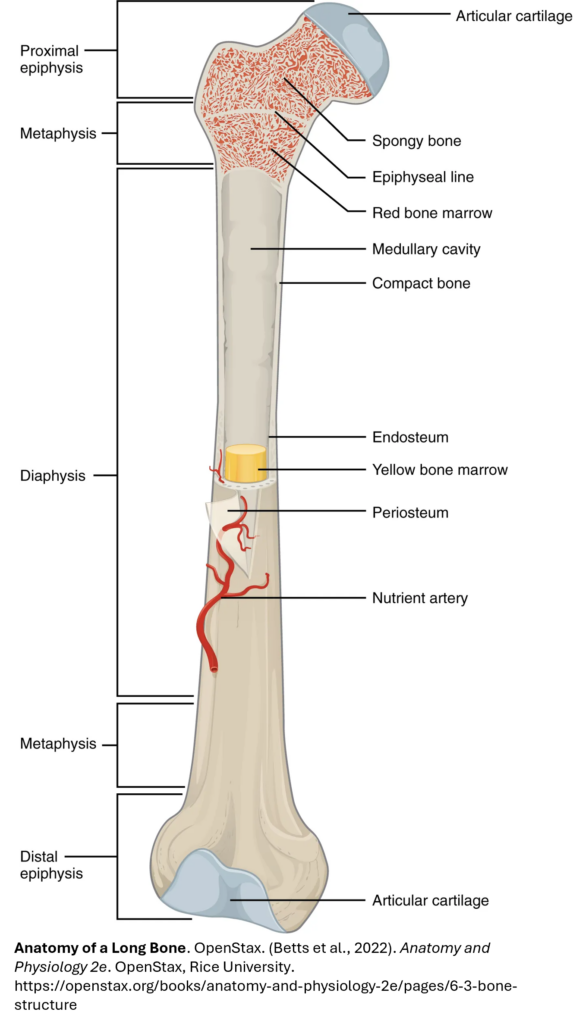

Before diving into 3D exploration, take a close look at the labeled image. It highlights the key regions of a long bone. A typical long bone has five zones: the diaphysis, two metaphyses, and two epiphyses as described below.

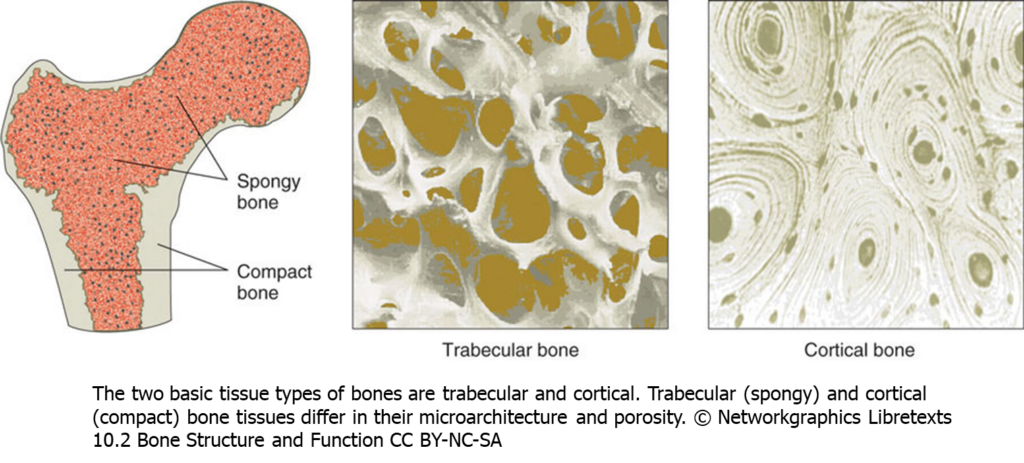

- The diaphysis: This is the long, tubular shaft that stretches between the proximal and distal bone ends. Its walls are made of dense compact bone, built to withstand the stress of everyday movement.

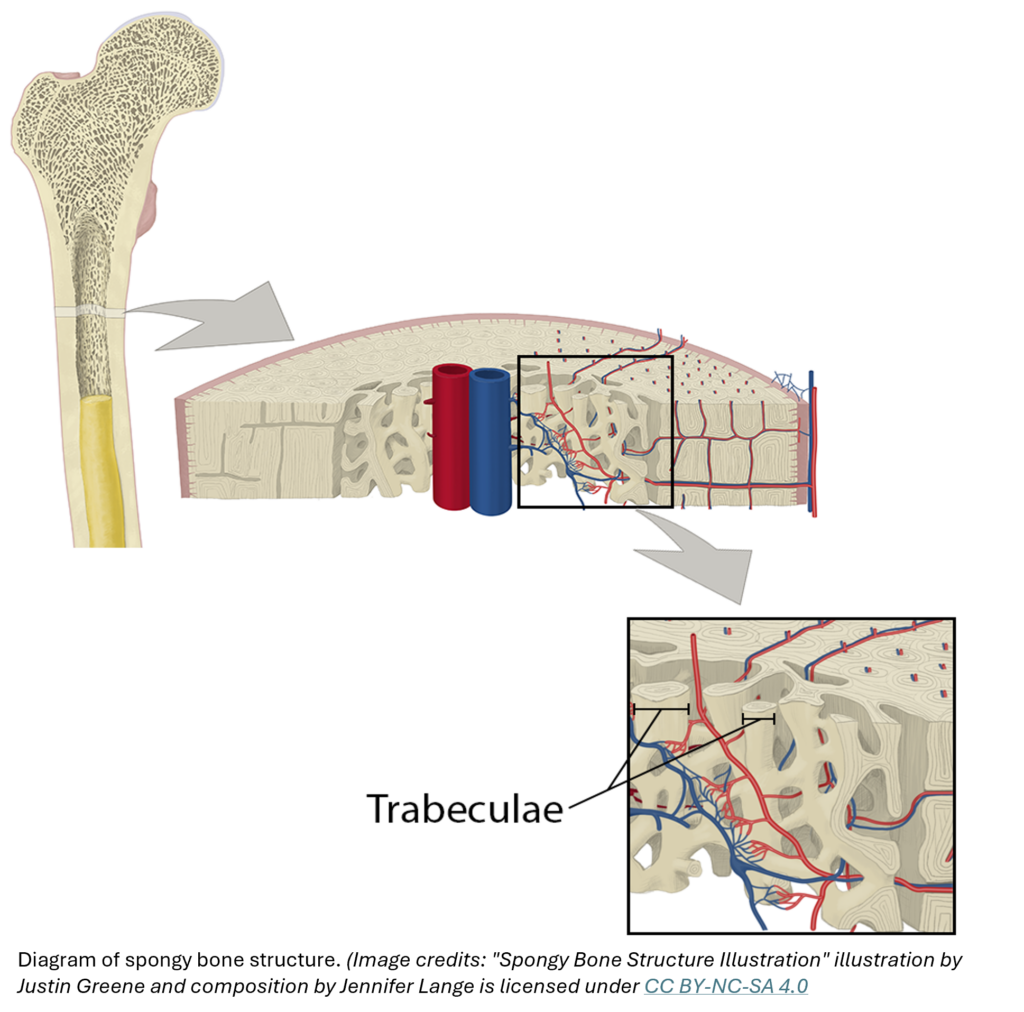

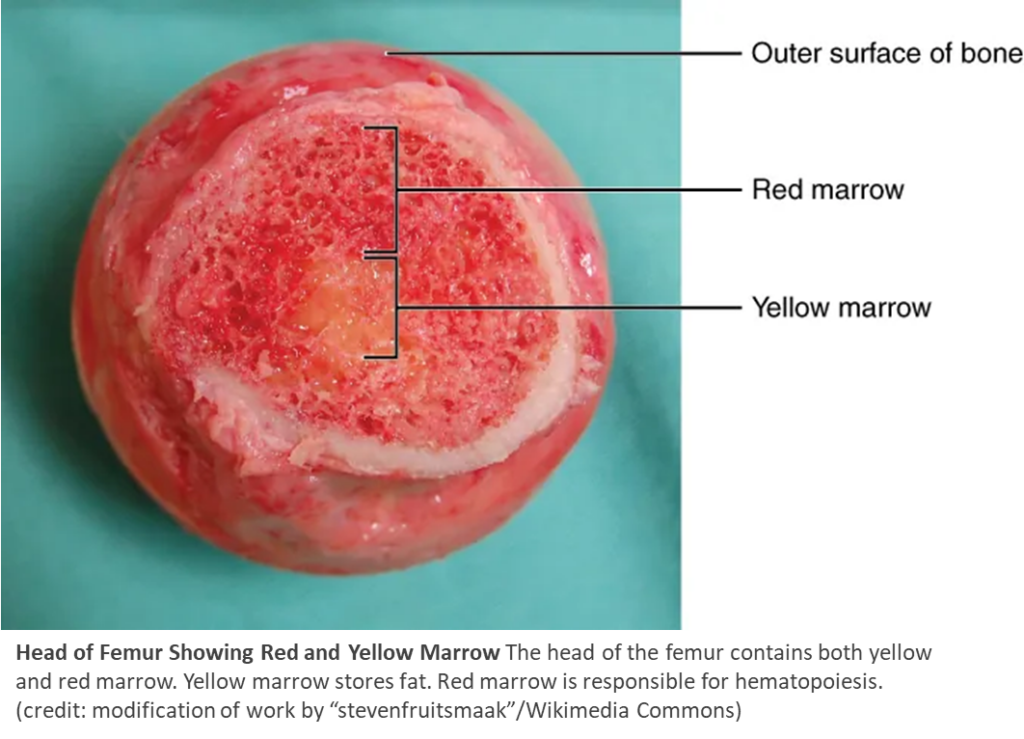

- The epiphysis: The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural = epiphyses), which is filled with spongy bone. Red marrow fills the spaces in the spongy bone and is the site of developing blood cells (red and white) and platelets. The ends of epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber to form joints with other bones. The epiphysis extends from the end of the bone to the epiphyseal plate (growth plate in children) or epiphyseal line (in adults).

- Metaphysis: This is the area where growth occurs in children, containing the growth plate (epiphyseal plate). It is a highly metabolic and dynamic region that contains a diverse population of cells involved in bone growth and blood formation. It contains spongy bone and red bone marrow.

- The metaphyses contain the epiphyseal plate, which is a layer of hyaline (transparent) cartilage in a growing bone. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18–21 years), the cartilage is replaced by osseous tissue and the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line.

- In adults, it transfers loads from weight-bearing joint surfaces to the diaphysis.

Types of bone marrow

- Red marrow: The primary site for hematopoiesis, or the production of all blood cells. In adults, it is found in spongy bone tissue, such as the heads of the femur and humerus.

- Yellow marrow: Primarily consists of adipose tissue (fat cells) and serves as a storage site for energy in the form of triglycerides. It is found in the medullary cavity of long bones.

Other Key Features

Medullary Cavity

A hollow space within the diaphysis lined by spongy bone and filled with yellow marrow, which stores fat and serves as an energy reserve. It also contains mesenchymal stem cells that can make bone, cartilage or muscle cells. In children, it is almost completely filled with red marrow (red marrow is replaced with yellow marrow with age).

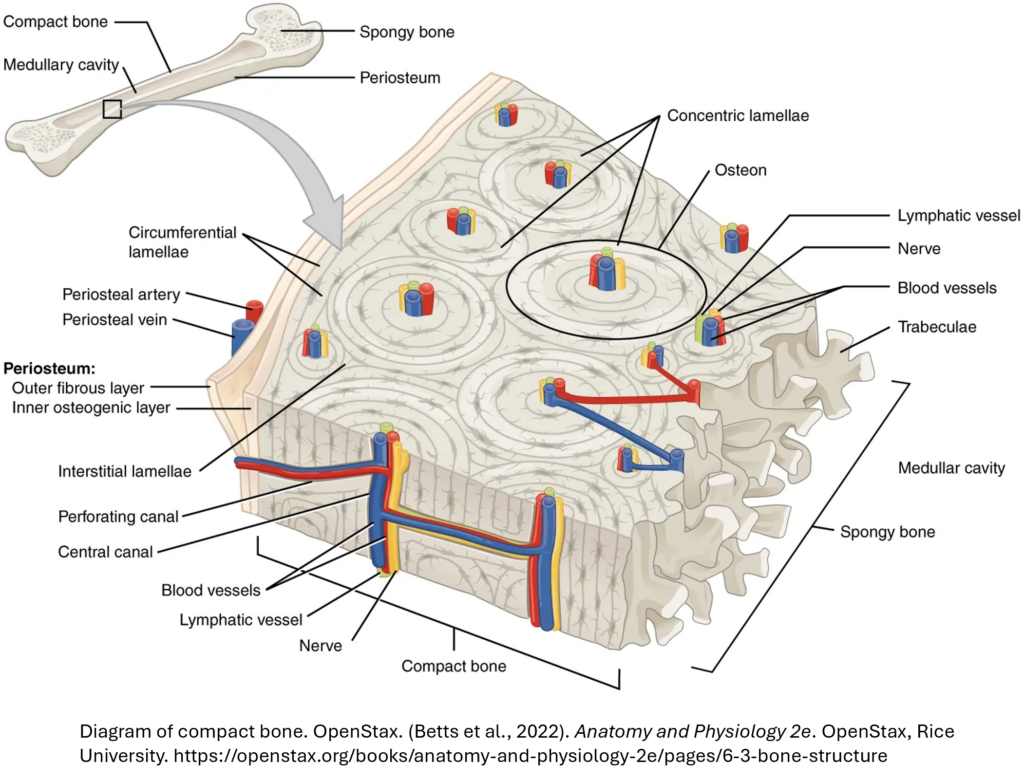

Periosteum

A fibrous membrane covering the outer surface of the bone (except at joint surfaces). It has:

- An outer fibrous layer of dense regular connective tissue for protection.

- An inner osteogenic layer containing bone-forming cells.

It also houses blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels, and serves as an attachment point for tendons and ligaments.

(Betts et al., 2022)

Endosteum

A delicate membrane lining the medullary cavity, where bone growth, repair, and remodeling occur. (end- = “inside”; oste- = “bone”)

Fun Fact: The femur and tibia are the body’s strongest long bones—they carry most of your weight when you walk, run, or jump! This structural organization allows long bones to be both strong and lightweight—perfectly suited for movement, support, and protection.